"The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated."

--The US Dollar

Among the factors that influence the asset mix of a thoughtfully designed global macro portfolio, the manager’s long-term dollar thesis is key.

As for our long-term (the next cycle) macro view, we -- despite our opening quote -- anticipate a weaker trending dollar... Which, as you'll see in Part 5, can make for a global investment setup rich in opportunity.

So why the weak-dollar view?

Well, and make no mistake, it's definitely not because the dollar is in any near-term risk of losing its reserve currency dominance.

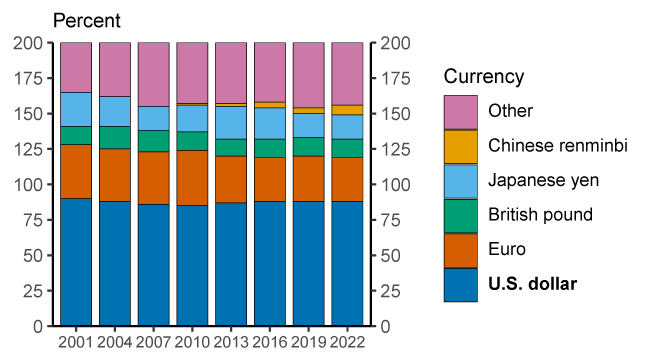

Per the Bank for International Settlements (HT The Fed), the US dollar (blue bar below) -- in terms of its share of global foreign exchange transactions -- hasn't skipped a beat:

"The many sources of demand for U.S. dollars are also reflected in the high U.S. dollar share of foreign exchange (FX) transactions. The 2022 Triennial Central Bank Survey from the Bank for International Settlements indicated that the U.S. dollar was bought or sold in about 88 percent of global FX transactions in April 2022. This share has remained stable over the past 20 years (Figure 9). In contrast, the euro was bought or sold in 31 percent of FX transactions, a decline from its peak of 39 percent in 2010.11

Figure 9. Share of over-the-counter foreign exchange transactions

Note: On a net-net basis at current exchange rates. Percentages sum to 200 percent because every FX transaction includes two currencies. Legend entries appear in graph order from top to bottom. Chinese renminbi is 0 until 2007.

Source: BIS Triennial Central Bank Survey of FX and OTC Derivatives Markets."

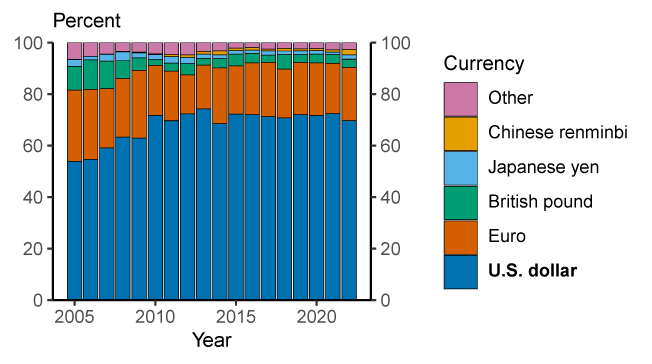

Same goes for foreign currency debt issuance:

"Issuance of foreign currency debt—debt issued by firms in a currency other than that of their home country — is also dominated by the U.S. dollar. The percentage of foreign currency debt denominated in U.S. dollars has remained around 70 percent since 2010, as seen in Figure 8. This puts the dollar well ahead of the euro, whose share is 21 percent.As for global trade, the dollar's dominance remains "overwhelming."

Figure 8. Share of foreign currency debt issuance

Note: Foreign currency debt is denominated in a foreign currency relative to the country of the issuing firm (not the location of issuance). At current exchange rates. Data are annual and extend from 2005 through 2022. Legend entries appear in graph order from top to bottom. Chinese renminbi is 0 in 2005.

Source: Refinitiv; Board staff calculations."

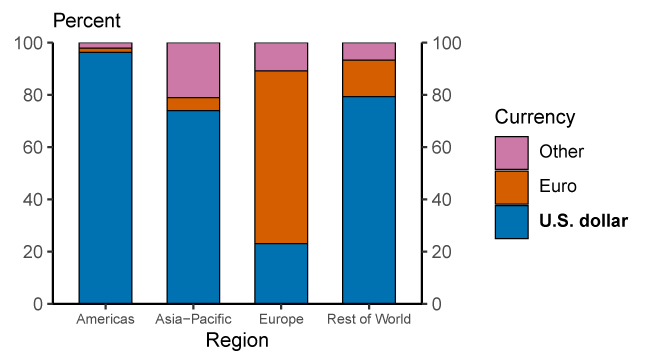

"The U.S. dollar is overwhelmingly the world's most frequently used currency in global trade. An estimate of the U.S. dollar share of global trade invoices is shown in Figure 5. Over the period 1999-2019, the dollar accounted for 96 percent of trade invoicing in the Americas, 74 percent in the Asia-Pacific region, and 79 percent in the rest of the world. The only exception is Europe, where the euro is dominant with 66 percent.

Figure 5. Share of export invoicing

Note: Average annual currency composition of export invoicing, where data are available. Data extend from 1999 through 2019. Regions are those defined by the IMF. Legend entries appear in graph order from top to bottom. The value for Europe includes within-euro area trade.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade; Central Bank of the Republic of China; Boz et al. (2020); Board staff calculations."

And if the above doesn't convince you, consider where the world's countries choose to stash their foreign exchange reserves:

Although, I will say that, in the FX reserves space, the dollar has given way, a bit, over the past 20 years.

And, lastly, in a year where I've fielded more questions about the state of the dollar than any I can recall, well... take a look at this 5-year graph of DXY (the US dollar index):

So, again, why the weak-dollar view going forward?

Well, to clarify, when I say "going forward" I'm referring to what we believe the prevailing trend will be during the next cycle... In the near-term -- the rest of the current cycle (we’re in the late stage) -- the dollar will be somewhat range bound... Declining as inflation and, hence, interest rates continue their descent, then catching a bid if/when recession ensues… The latter explains our reluctance to add measurably to weaker-dollar plays right here.

Beyond whatever's left in the current cycle, here's where we're coming from.

For starters, from a very long-term perspective, the US government debt situation, combined with trillion dollar annual budget deficits as far as the eye can see, is a problem... Particularly when you consider the one chart above -- FX reserves held in dollars -- that calls the dollar's long-term dominance into question.

I.e., in a world where foreign governments are seeking alternatives to the dollar (we'll discuss gold in a bit), one has to wonder if there'll be sufficient demand -- at reasonable rates -- to fund the federal government ad infinitum!

"At reasonable rates" being the operative words there.

I.e., if indeed the world's losing its appetite to hold massive quantities of US treasuries, then, by virtual default, the market's going to make them more attractive to own -- i.e., interest rates virtually have to go higher.

And just imagine such a (higher interest rate) future -- imagine the ever-growing expense -- where trillions in future budget deficits have to be financed, on top of tens of trillions of existing debt coming due (over time) that has to be refinanced!

This year's interest expense accounts for 16% of the federal budget -- that's 169 billion of those US dollars!

Now, granted, it is worth noting that roughly 60% of the total $31 trillion the federal government owes is held by US individuals and institutions -- so the interest paid on that amount is going back into the US economy.

All things considered, however, suffice to say that long-term we may have us a problem.

Now, to be clear, we have been here -- debt to GDP over 100% -- before.

Take a look:

That 1940s episode was of course the result of WWII, but with the massive post-war government spending to follow, what gives? How did the debt/GDP ratio literally collapse from the mid-1940s to the early-1950s?

Well, frankly, that "massive government spending pressure to follow" demanded something be done to arrest what might otherwise be disastrously runaway interest rates.

And here's that something: (Yes, I know, we've pounded on this one before, but it's been awhile 😎)

"Upon the entry of the United States into World War II, the U.S. Treasury faced the task of financing an enormous debt expansion. The Federal Reserve assisted the Treasury in this effort by implementing a form of yield curve targeting, capping interest rates at several points along the yield curve: from 3/8 percent on T-bills to 2½ percent on long-term bonds. This pattern can be seen in figure 1. Rates were set to be slightly higher than those that prevailed in November 1941, just prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To implement this policy, the Fed purchased Treasury securities as necessary to prevent interest rates from rising above the caps. In particular, the Fed acquired very large amounts of Treasury bills from 1943 to 1947, as can be seen in figure 2. Figure 3 shows that the Fed did not acquire nearly as large a share of other Treasury securities, at least until 1947 when the T-bill rate was raised. From 1943 to 1947, private investors evidently preferred longer-term Treasury securities that carried higher interest rates, still featured very high liquidity, and had no real risk of capital losses given the Fed’s rate caps. The Fed’s purchases were carried out in the secondary market, in many cases by banks buying bonds from the Treasury and immediately reselling without profit to the Fed (Murphy, 1950, pp. 212–213)."

In essence, while of course the Federal debt pile continued to grow that whole time, the Fed "allowed" inflation, and, hence, GDP to run hot enough -- above the then-fixed rate on treasuries -- to outpace the rising debt... In other words, the US inflated away its debt (to GDP) worries.

In our view, while they may do it in stealthier fashion than the Fed of the 1940s, it's not remotely out of the question that present-day policymakers will be essentially forced into similar measures in the not too distant future... Which of course would pose quite the headwind for the dollar.

And given that higher inflation intuitively means a weaker dollar (intuitive, yes, but not always the case), we should probably revisit our own go-forward structural inflation thesis:

"...amid what may be a period of relatively low velocity of money, heavy debt burdens, and, we presume, further technological advancement -- I see increasing odds that we're at long last on the cusp of something meaningful (but not 1970s meaningful, mind you) with regard to structural inflation risk:

- Increasing populism (a serious headwind for global trade -- in both goods and in labor).

- A continual stimulating of the economy via fiscal policy (facilitated by easy monetary policy) -- demanded by a politically-powerful populist movement.

- China maturing into a service-oriented, consumer-driven economy (while moving away from providing cheap labor and goods to the outside world).

- The Fed's fear of bursting present asset and debt bubbles were it to implement traditional inflation-fighting measures -- thus willing to fall notably behind the inflation curve well into the foreseeable future. In fact, I personally place better than 50/50 odds that if indeed a long-term trend of rising inflation emerges, that the Fed will revert to yield curve control (buying up the price (down the yield) of longer-term treasuries) to control lending rates that, were they allowed to rise, would themselves produce a headwind to rising inflation.

- The trillions of dollar-denominated debt sitting on foreign corporate balance sheets inspiring an active campaign by the Fed to keep the dollar at bay, in an effort to avert what could otherwise turn into very messy global currency crises.

- The reticence of producers in the metals space to aggressively expand capacity despite rising prices: Speaks to the devastation they experienced post the ‘08 to ‘11 China building boom.

- The political/environmental headwinds for fossil fuel producers to expand capacity.

Now, all that said, before we settle into that structurally rising inflation scenario (if indeed that's where we're headed), I look for a notable calming of the thrust we're presently experiencing -- as the worst of the production bottlenecks subside -- inspiring a chorus of I-TOLD-YOU-SOs from the "it's transitory" camp.

- Inflation being the US’s historically-preferred mechanism to reduce heavy federal debt burdens.

Thereafter I suspect we'll see inflation settle into a steadily rising structural trend, and in the process fuel what will likely turn out to be the next longer-term commodity supercycle."

Now, make no mistake, as we've been pointing out along the way (the above was penned in October '21), it was, and remains, our view that in the short-run inflation's coming down... But rather than being a reason for the equity market to party, as it has, it ultimately stems from what typically brings a bear market to its knees, i.e., recession...

It's the ensuing cycle -- a most exploitable one, we anticipate -- that will make true believers out of those who today insist that, despite all that we bullet-pointed above, nothing's really changed.

Time will tell.

Here's some supplemental commentary from two of our premium research providers (we'll tackle the setups we like going forward in Part 5):

BCA Research's FX team on their 2024 outlook:

"The dollar will continue to weaken in the near term as global manufacturing bottoms, but will start to strengthen in the first half of 2024 as it sniffs out a pending recession (Feature Chart).

Any recession will likely be shallow and short-lived suggesting the DXY will not take out its 2022 highs. But as sentiment towards the dollar deteriorates, it will pay to be contrarian.

Once the recession is over, the dollar should secularly decline.

A key driver of dollar downside will be expensive valuations and a deterioration in balance of payments. De-dollarization will also slightly weigh on the greenback.

In terms of currency winners in the near term, we like Scandinavanian exchange rates, especially the Norwegian krone. Petrocurrencies are also a nice call option on any upside surprises to the oil price. The Japanese yen will fare well in 2024.

Gold will benefit from the eventual decline in the dollar, but silver is our preferred precious metals vehicle."

Regarding gold and silver, we own both... However, we prefer gold right here, while recession risk remains elevated.

"To the debate over whether there is a shift among the BRICS+ countries to use a transaction currency other than US dollars, it is happening by the way, there was a story from BN yesterday that said Brazil is now the number one global exporter of corn to China, passing the US.

Whether this sustains itself or not many times depends on the quality of harvest and price but assume many of these corn bushels were paid with renminbi that Brazil is now happy to accept.

They are happy because it both diversifies their currency reserves but it also provides them with renminbi to in turn buy stuff from China as after all, China still makes most of the world's stuff.

De-dollarization, however it plays out from here in terms of timeline and extent of usage, is for real."

We do agree that "de-dollarization" is for real, but is it an imminent threat the dollar's world reserve currency status? Unequivocally not... But it does indeed support our long-term weaker-dollar thesis.

One last point we should address... There's this chorus out there who sees a global dollar shortage, amid a massive pile of dollar denominated debt on foreign corporate balance sheets (see the 5th bullet point in our inflation narrative above), and, hence, makes a case for a stronger-trending dollar as, for example, those borrowers will be forever scrambling to accumulate it to service their debt.

What this particular strong-dollar camp typically fails to point out is that the US runs a large capital account surplus -- i.e., foreign entities buying US assets -- that to some degree balances that debt situation... Not that each borrower in and of itself has sufficient ownership in US assets to balance things out, but, nevertheless, there are meaningful US dollar positions that can -- push come to shove -- be liquidated if deemed necessary, or desirable... And we should not underestimate the Fed's wherewithal to provide liquidity (that 5th bullet point above) -- via FX swap lines (they did it big time during covid to keep the dollar at bay) -- when and where needed...

At the end of the day, the US actually needs inflation, and, at a minimum, a steady, or (far more likely, in our view) weaker dollar for years going forward.

And speaking of liquidating US assets, if indeed the dollar weakens (or even stops rising) in the years ahead, that makes for a serious tailwind for foreign asset markets (significantly cheaper emerging market equities in particular).

In fact, a rotation to more attractive valuations abroad will exacerbate, if not itself initiate, weakness in the dollar.

We'll explore those prospects in Part 5 6.

No comments:

Post a Comment